Go and buy Batchoy at Reegals. Bring the pitcher.

I am a probinsyana³ born in 1998 from a city called Kabankalan, fifty-five miles south of Bacolod City, on a sock-shaped island called Negros, originally named Buglas. When I was growing up, my mother or father would often instruct me and my two other siblings to buy “pamahaw,”⁵ a Hiligaynon term which means “afternoon snacks.” Some of my fondest childhood memories include bringing pitchers and containers to a beloved local restaurant (such as Reegals) for takeout soup and other food or bringing a reusable “rice sack bag” to the market. Basta mabutangan, pwede masudlan—anything that can hold something can be a container. Now, you may think it is absurd that soups would be placed in pitchers meant for drinks, but during that time I did not question why the community had developed this system of just leaving those containers at restaurants and market stalls, fully entrusting them to come back to us. The isolation of the island made it slow in catching up to the trends and advancements of the bigger cities; we had not yet been overtaken by the “trend” of single-use plastics. But that trend definitely caught up with us in a big way.

There used to be a strong culture of recycling on our island. Most memories of my time on this island include my grandparents of both sides, especially my Lola Gloria, whom I most vividly remember would make pillows by stuffing them with cotton coming from the fallen fruits picked from the big kapok⁶ tree beside our house. It was an afternoon pastime of hers for years. Eventually, as single-use plastics caught on, those cotton stuffings were replaced with plastic packaging of various sizes, which then would be meticulously cleaned, folded up, cut into bits, packaged, and then stuffed in those pillows. When I would ask her of that meticulous process, she would always say, “Kanugon”—It’s such a waste to throw it away, staying true to the old and timely Filipino saying “May pera sa basura.” There is cash in every trash.

It was at Kampo Klima (Camp Climate) in 2018, a province-wide environmental initiative youth camp, that I was exposed to the bigger issue of plastic waste. I learned that our whole island, not just the coastal areas but even the inlands, was at risk of being submerged due to the alarming rising seawater levels. I also saw photos of suffering land and sea creatures, such as turtles and birds tangled up in nets and plastic straws, dead whales found with huge amounts of plastic waste in their stomachs, and sadly, so much more. From that moment, my perspective shifted. I wanted to be an active advocate of the cause. I started by looking for eco-friendly alternatives to plastics, such as using reusables and pasadors (cloth napkins), and starting conversations with fellow advocates. I hoped that with just a little effort, that nightmare of the submerged waters of Kabankalan would not materialize.

Almost half a decade of practicing, observing, and documenting my experiences with reusables in different places has sparked endless discussions and more acceptance in my own different circles. It was one discussion with a friend, in fact, who wished to take the same steps that sparked the idea to create a guide for people who want to embrace zero-waste practices but don’t quite know where to start. I want to create an open community map where everyone can share their favorite spots and the zero-waste practices that those places embrace. It will be a hub for people to share their tips and ideas, a place to rethink solutions so others can have an easier time navigating zero-waste practices. This idea is inspired by the Wala Usik movement7 (“nothing wasted” in Hiligaynon), a community initiative of Philippine Reef and Rainforest Conservation Foundation, Inc. (PRRCFI). I was also inspired by how Angel Mata of Low-Impact Filipina⁸ documents her low-waste journey as well as a local Facebook community group named Buhay Zero-Waste (ZW) Community⁹, both of which helped me immensely in my early years.

To learn more about what PRRCFI does, follow them (linktr.ee/prrcfi) or check out their free online guides. Examples of these guides include “Ibalik ang Wala Usik: The Business of Reducing Waste” at prrcf.org/walausik in celebration of National Zero Waste Month, and “Women Waste Workers for Wala Usik” at prrcf.org/wow. The latter is a gender-responsive solid waste management guide released for International Women’s Month.”

‘Cause the Pins Bring Back All the Memories. Physically Wala Usik pin-mapping everything from memories and experiences and more ideas on the side! Look! A mini (pin) bar graph.

‘Cause the Pins Bring Back All the Memories. Physically Wala Usik pin-mapping everything from memories and experiences and more ideas on the side! Look! A mini (pin) bar graph.

Data from the Roots

To work toward this community map, I needed data. I started with a data science scholarship from the For the Women Foundation¹⁰ and quickly learned that the more data we collected, the better insights we could discover. However, I struggled as a junior data scientist with buzzwords that had vague descriptions, like “data science” (DS), “open data,” and “machine learning” (ML). I knew I wanted to do something with data and climate justice, but I struggled with where to direct my focus specifically. That was when I realized there was already quality data that I could work with!

One of the initial steps I took was laying out all of my experiences (wins shared online, documentation, notes, narratives, and observations) and trying to make sense of them, developing a systematic and organized way to better “analyze” those data and create a meaningful dataset. This naturally meant retracing all of those experiences. My usual workflow started with personally going to the area as a customer and observing how things worked. I would take note of how the store utilized packaging (especially the plastics), and eventually I would come back with the alternative solutions after grappling with what worked and what didn’t.

As I progressed, I created additional features to my data set, such as labels for tried-and-tested alternatives to single-use plastics and other initiatives that contribute to sustainability. This information can be found online on mapping apps, such as Google Maps and OpenStreetMap, and on the stores’ social media pages, which can be verified upon a visit. Examples of features include: markers of areas that offer cashless payment systems (e.g., GCash, PayMaya); areas that actively participate in eco-friendly initiatives (e.g., encouraging consumers to use their own eco bags, having their own Bag-Free Sundays, using as little plastic as possible, etc.); and establishments that accept reusables as alternative options. There is a lot more data that could be included, such as the availability of refilling stations and accessibility options as well as a place for people in the community to share their own insights and pro-tips. This “slow data” effort required conscious data work efforts at a personal level, from collection to analysis. If I had just relied solely on online data without having the physical experience myself, I would not have realized that so much of the data online was outdated or missing, especially in places poorly mapped. This helped me realize the value of this effort, both on- and offline.

After collecting this data, the community guide and map will cohesively put it all together, making the data and the work accessible and visible to a wider audience. As my friend Dairin once said, “In order to be seen, you must be visible.” My goal is to create a map that is interactive, encouraging its users to start their own initiative to reduce their plastic use and seek alternative solutions. It is also a great way to introduce open data and learning in a way that fosters community data, for the people and by the people. The map will display knowledge from the locality with nuances from the community, and thus it can help preserve past practices, nourish present practices, and inspire hope for future practices. This resource can start conversations among community members and lead to a wider discussion about other environmental initiatives.

At the moment, I have mapped out some places in my community in print format, using paper and other forms of mixed media, and highlighted the practices and stories behind them.This helped me to get a sense of the meaning going into work while at the same time improving and shaping the project.

On the Intersections of Data (and the Life)

As I navigate this low-waste journey, going through the continuous and conscious act of interacting with the environment, I have come to several realizations. At first it was exciting, thinking of alternative environmentally conscious solutions, but as time went by, I realized that a whole systemic routine is also challenged in the process—not just affecting the circles I am part of, but also breaking the norms of the larger community.

In truth, the act of taking a seemingly small step, such as using reusable containers as opposed to relying on single-use plastics, actually disrupts the consumer-retailer relationship. When you are used to doing something and are faced with the unusual, it causes you to step back, think, and question. You have to face weird looks when you anxiously mention, “Diri lang nakon ibutang Tita/Tito”—You can place it here in my container. You will receive unsolicited remarks as you bring your reusables everywhere, and this may cause others to feel uneasy about their own behavior (“Sorry if we’re using these single-use plastics!”). It can make you feel alienated and uncomfortable just for wanting to do something small. But among those encounters, there are also those great conversation starters that make up for it, especially with those we meet on a day-to-day basis.

One great example was a woman I met who owned a street food stall. Pre-pandemic, she was one of those that gave me weird looks as I anxiously asked, “Tita, pwede diri mo lang ibutang ang kwekkwek?”¹¹—Auntie, can you put it here in my lunchbox?—but nevertheless, she complied. After consecutive visits, she became more open and supportive of my initiative, opening the conversation by asking, “Diin imo bulutangan?” (Where’s your container?) or telling her companions and other customers, “Ah amo ni amon suki¹², may dala na iya tupperware” (Ah, there she is! One of my loyal customers, who always brings her containers along). Other vendors did not even bat an eye, because for the elders, reusable container use is really just a return to an older practice. These simple experiences also tap into the community’s creativity as we try to navigate back to the time of our ancestors that used less—or, if possible, no—single-use packaging.

Just like my interactions with vendors, doing a conscious data analysis requires viewing data through the point of view of others and trying to meet others halfway. We need to acknowledge that what works for some doesn’t work for others, but it is important to find a common ground. It is easy to see data as just numbers or lines in our databases, or to only focus on the technical details of our work. In doing so, we often unconsciously overgeneralize and ignore the details that are perhaps most important to the community. As Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren Klein emphasize in their book Data Feminism, “Embrace pluralism. [. . .] The most complete knowledge comes from synthesizing multiple perspectives, with priority given to local, Indigenous, and experiential ways of knowing.”¹³ This map indeed aims to embrace that pluralism by putting the community at its center.

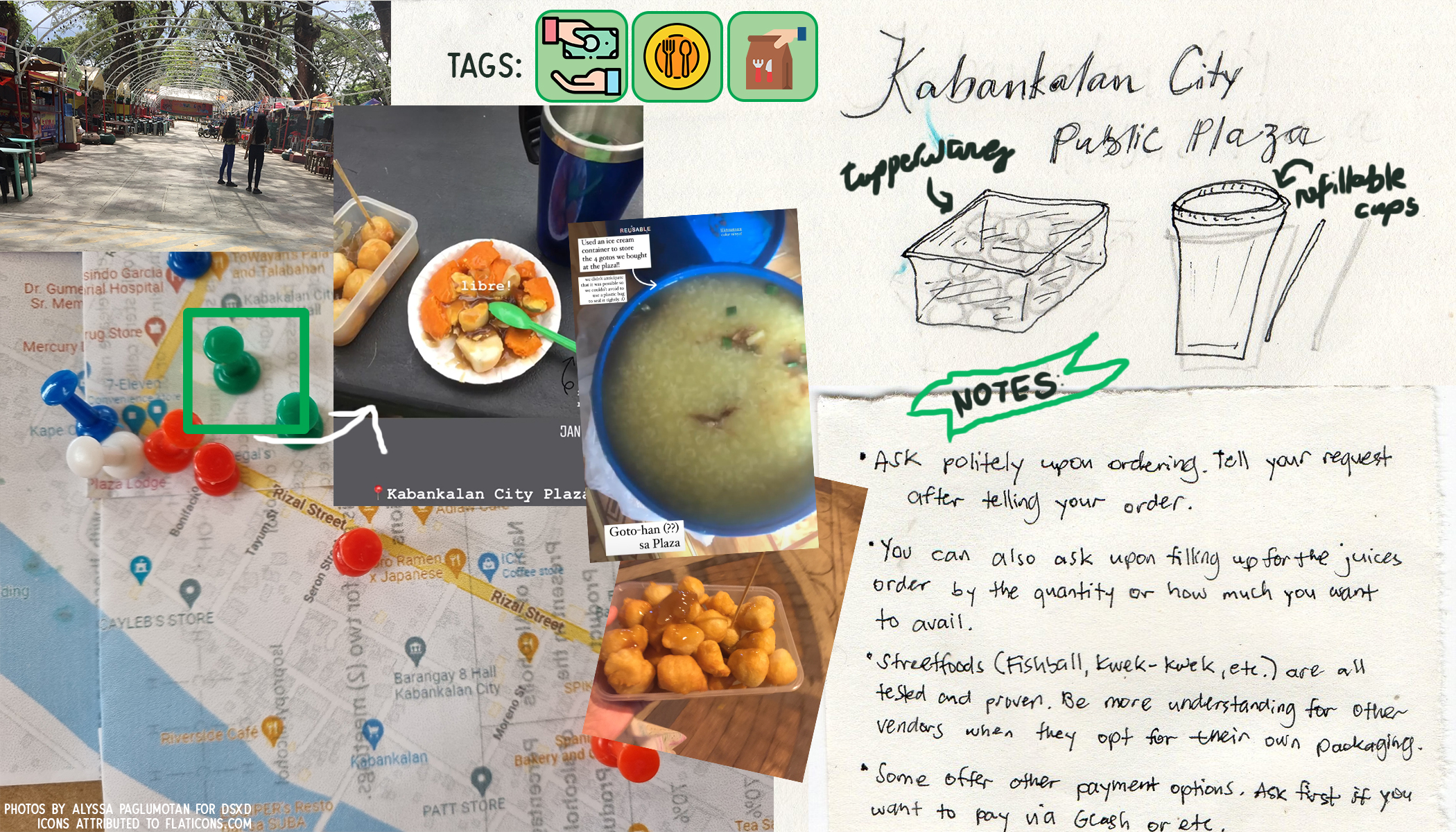

Example Card of how it would look on highlighting each place's low-waste method through friendly tips, indicator tags, photos. Sketch of the Kabankalan City Plaza.

Example Card of how it would look on highlighting each place's low-waste method through friendly tips, indicator tags, photos. Sketch of the Kabankalan City Plaza.

Sprouting from the Ground, Growing Upward and Beyond

The experience of working on this project has helped me get to know more of my community, share my passion, and encourage others, but at the same time I acknowledge that there is still a lot of work to be done. Plastic use is deeply embedded in our systems, holding us in a chokehold, and the rise of single-use plastics heightened during the pandemic.¹⁴ I, too, have struggled with the complexities of practicing low-waste efforts in the face of the pandemic.

However, I am not alone in doing this data work. A collective voice is watching over the climate movement, using their own skills and data to inform initiatives for the community. For example, the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA) releases reports, such as this 2019 report, that give a clearer picture on how waste assessments and brand audits from different cleanup initiatives (coastal cleanups, etc.) create a more detailed picture of how to combat the larger problem of plastics.¹⁵ From those reports, it helps organizations like PRRCFI to think of solutions such as the Wala Usik Tiangge15 as an answer to the “tingi-tingi” (“sachet economy”) ecosystem.

With all of these initiatives, both individual and collective, we can further discuss and discover what practices are sustainable. Whether they are big efforts or small efforts, every data point (and reusable container) helps.

Wait a minute, I'm going to bring my container and water bottle.

Bio:

Alyssa Melody Paglumotan is a passionately curious Filipina currently on a quest to be a data scientist for social good. She aims to help make data science interdisciplinary and open for all. So far up her sleeve, she is a woman in tech, an educator, a junior data scientist, a science communicator, a write, a volunteer for various organizations (10+ years and counting), and so much more, always open to unlearning and relearning. Currently, she’s the head communications manager of GDG Bacolod, a local tech organization that shares her vision to empower women in tech and all in the province.

References / Footnotes

- A noodle soup made with pork offal, crushed pork cracklings, chicken stock, beef loin, and round noodles.

- A beloved local restaurant in the city.

- Feminine term for someone from the province.

- The name Buglas came from an old Hiligaynon word meaning to “cut off,” from the island being believed to have been cut off from a larger land due to the rising waters from the Ice Age. The name of the island was changed to Negros by the Spanish colonizers. The Philippines has a very complex history with colonialism (most notably, the Spaniards, Americans, and Japanese) and the name Negros Island.

- The same word exists in Filipino, the dominant language in the Philippines, as the result of long-term influence of colonization. Not to be confused, Hiligaynon and Filipino are just two of the 187 languages in the Philippines, with Filipino as the dominant language used in the country. Hiligaynon is mostly used in the Visayas and Mindanao areas of the country, notably attributed with the Panay and Negros Island of Western Visayas. There are various debated topics surrounding language vs. dialect.

- We would call it the doldol tree in Hiligaynon.

- https://www.inclusivebusiness.net/ib-voices/zero-waste-innovations-wala-usik-model-philippines

- https://m.facebook.com/lowimpactfilipina/about/

- https://www.facebook.com/groups/buhayzerowaste/

- A nonprofit Philippine foundation that empowers Filipinas by equipping them with tech skills, most notably in digital marketing and data science, through scholarship grants.

- Fried orange quail eggs, a street food delicacy, which also uses hard boiled eggs as an alternative. https://panlasangpinoy.com/pinoy-street-food-orange-egg-tokneneng-qwek-kwek-kwek-recipe/

- Term for a loyal customer, one who regularly visits a certain store/establishment.

- https://data-feminism.mitpress.mit.edu/

- https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/9e4fd47f-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/9e4fd47f-en

- https://www.no-burn.org/wp-content/uploads/PlasticsExposed-3.pdf

- https://www.no-burn.org/wala-usik-zero-waste-sari-sari-stores/